This piece presents a new family of hash functions from sequences of letters to vectors of numbers which are both locality-sensitive and algebraic. The hash functions can also be used with other inputs such as images, time series, multi-dimensional arrays, and even arrays with varying dimensions. We’ll go over examples and see some animations.

Intro

Sometimes we are handed a collection of objects and we need to find which are similar and which aren’t. For example we might be looking at articles in English on Wikipedia, and we want to find pairs that are very similar. Or maybe we’re looking at DNA sequences and we’re interested in understanding similarity between species. Further afield, we might have a large collection of image files and we want to check if we have one that is similar to an image that someone sent us. Maybe it’s stock price series over 10 ten years instead of images. In all these cases we aren’t looking for exact matches, but rather similar objects, where we have some notion of similarity.

Levenshtein distance

If our collection of objects is that of strings, meaning sequences of letters, then there are a few such notions of similarity that are popular, the most prominent being Levenshtein distance. The Levenshtein distance between two strings is the number of operations needed to go from one to the other, where the allowed operations are adding a letter, deleting a letter, and modifying a letter. For example, the Levenshtein distance between “kitten” and “sitting” is 3, and this example can be found on the Wikipedia page for Levenshtein distance.

The Levenshtein distance is very useful when quantifying the distance between two strings. Unfortunately, it is also pretty time consuming to compute, especially if the strings are long. Computing the Levenshtein distances of all pairs from a large collection of strings is time consuming and often infeasible.

Locality-sensitive hashes and MinHash

Instead of computing the distance between all pairs of strings from a collection, we can employ the idea of first hashing, meaning mapping, all the strings with a function that is locality-sensitive. This means that the hashes of a pair of similar strings are also similar, and the hashes of unsimilar strings are likely to be unsimilar. If we have such a hash function, then we can first apply it to all strings in our collection, and then go over only those pairs of strings whose hash values are already similar. This idea can cut down are search space considerably, turning intractable problems into tractable ones.

The most famous locality-sensitive hash function is MinHash. The actual definition is technical, and I want to keep the technical parts of this piece to the new family of hash functions, so you can read more on its great Wikipedia page.

I do want to note one thing about MinHash: it is commutative, meaning order doesn’t matter. For example, if we’re using MinHash by looking at words in strings, then the hash of the sentence “don’t give up, you matter” is the same as the hash of the sentence “you don’t matter, give up”.

New locality-sensitive hash functions

Letter counting

Before delving into interesting new locality-sensitive hash function, let’s look at a subset of the family that is old and known – letter counting.

Given a large collection of strings, we can count how many times each string contains the letter “a”. We can then go over pairs that have a similar number of a’s and compute their Levenshtein distance. This idea can cut down out search space by some factor. We can also count the number of b’s in each string, and then use the two counts together to cut down the number of pairs we go over. We can do this for a few letters, though generally speaking we can’t use too many since it’s not trivial or clear how to enumerate only those pairs of strings that have a similar number of a’s, b’s, etc. We can use data structures such as k-d trees or R-trees.

Two things to note about this family of hash functions: first, it satisfies the first part of the (loose) definition of locality-sensitive hash functions appearing above, meaning similar strings will have similar counts of a’s, b’s, etc. On the other hand, it’s not clear that letter counting satisfies the other half of the definition, meaning unsimilar strings might not be that unlikely to have similar letter counts. This comes down to the statistical fact that letter frequencies in a given language’s texts might not be all that random.

Second, these hash functions are also commutative, meaning order doesn’t matter. In this case, it’s order of letters that doesn’t matter, so even the two words “admirer” and “married” have the same hash values.

– Rotations of a ball

– Rotations of a ball

We will now introduce the first new locality-sensitive hash function through an example.

Let’s take three letters: “n”, “e”, “t”. Also, let’s take a sphere, a ball in 3 dimensions. Our three dimensions have 3 axes. We’ll associate the letter “n” with rotating the ball along one of the axes, exactly 35 degree:

We’ll associate the letters “e” and “t” to rotating along the other two axes, like so:

We’ll mark a point at the top of the sphere, and apply the word net. What do I mean by apply? We’ll rotate the ball first using the rotation associated with “n”, then with “e”, then with “t”, like so:

Using this idea of assigning a sequence of rotations to letters we get a function from words with these letters to points on the sphere – we apply the rotations to the marked point at the top of the sphere and the word’s hash value is where we end up.

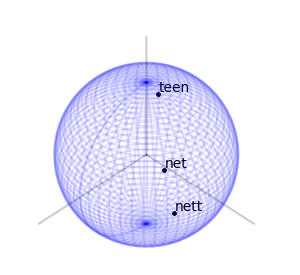

Let’s look at two other words’ sequence of rotations applied to the marked point at the top of the sphere. Here is “nett”:

and here is “teen”:

Here are the final positions of moving the marked point using the sequences of rotations associated with the three words:

We see that “net” and “nett” move the marked point to points that are slightly closer than where “teen” moves it to, matching our intuition on the similarity of these words. We can assign a rotation to each letter of the alphabet. We can go further and assign rotations to all ascii letters, or utf8 letters. Once we’ve done that, we have a rotation associated to every word, sentence, or string in general: to apply a string’s rotation to a point we first apply the rotation of its first letter, then its second letter, and so on.

Some notes: first, general rotations of a ball, meaning elements of , are not commutative – applying one rotation and then another is generally not the same as applying them in the reverse order. If we choose somewhat random rotations for each letter in our alphabet, then our hash function does not have the commutativity property that MinHash and letter counting do. The order of letters, words, etc. matters. This could be desired, or not, and depends on the use case.

Second, similarly to MinHash, for each choice of rotations to letters we get a new hash function, and we can combine multiple such choices in order to create a new hash function. In contrast to MinHash, the computational complexity grows linearly with the number of such choices, but this is a bit too technical for this piece.

Third, we can show that similar strings move a fixed point to similar positions. What follows is the most technical part of this piece: the maximum distance a rotation can move a point is the maximal eigenvalue of

. If we choose all our elements of

so that this maximum eigenvalue is

, for some small number

, then applying two strings

with Levenshtein distance

to a given fixed point can only result in a Euclidean distance not greater than

– each letter operation counts at most as changing two basic rotations.

Fourth, fixing a marked point and a small as above, experiments with Wikipedia articles hint that strings of length at least

end in a uniform-like distribution on the sphere. I can’t prove that this is indeed the case, and I’ve asked a simpler question on math.stackexchange, with no answers so far.

Fifth, if we actually use this method at the level of letters of an alphabet as the example above did, then we have a hashing method that is somewhat robust to typos, or in a biology context, to genetic mutations.

Finally, the choice of for the first example was for its ability to be easily visualized. We can use higher rotation groups –

– or any algebraic group. A nice property that the special orthogonal groups have is compactness. This means the numbers in our calculations can’t go crazy, and we should expect numerical stability. I also like that they’re connected. Another family of compact connected real algebraic groups is that of special unitary groups. Which is better practically is a question of performance of representation and multiplication of elements, and I don’t know the answer right now.

Hashing other things

DNA and RNA

These can thought of strings in specific alphabets, and the above applies verbatim.

– Fixed length vectors

– Fixed length vectors

Given a fixed length , we can choose

elements

in a connected compact real algebraic group

(such as

), such that the maximal eigenvalue of

for each element

is

, for some small

. Fixing some point

in a space on which

acts (such as a point on the unit sphere), we now have the following hash function on vectors of length

:

This will satisfy the property that similar vectors map to similar points. This can be proved using the same reasoning as that given above for rotations associated with letters.

We can use such a map to compress fixed length sequences. For example, there’s a lot of talk these days about Large Language Models (LLMs), and how they give rise to embedding vectors for texts. These can have high dimension, which can be brought down to, say, dimension 9 by using the above with a group like (each factor contributing 3 degrees of freedom).

Images of varying dimensions

If we a have collection of images of equal dimensions, then we can choose an ordering of the pixels of these images and use the previous section’s mapping. If the images in our collections have different dimensions, then we need to look for something else.

One idea goes as follows. Pick two non-commuting elements , for a connected real compact algebraic group

, such that the maximal eigenvalues of

and

are small. Enumerate the values of the pixels of each image as

(where we assume all images are gray-scale, though the following can also be done with more colors). We then have the following mapping:

This mapping satisfies a type of distance-similarity property.

Time series

The same idea works verbatim for time series, where we can interpret the element in the above formula as representing the passage of time. This mapping can, for example, be used to find pairs of stocks whose series of values are similar.

General monoid

We’ve been talking about algebraic groups, but we don’t really need inverses for everything that’s been said so far, we just need the ability to multiply elements. If instead of a connected real compact algebraic group we take the monoid and some random mapping from a given collection to

, then we recover MinHash. Yey!

Optimization and LLMs

In contrast to MinHash, using algebraic groups lends itself to optimization. If we have some property we want our mapping to satisfy, we can look for choices of embeddings that satisfy this property by using standard optimization algorithms.

For example, say we are interested in DNA sequences, and we want to choose four elements , one for each nucleobase, such that the embeddings of some sample of DNA sequences is relatively uniform on the sphere. We can create a loss function that measures the uniformness of these embeddings. This loss function is then a differentiable function in the coordinates of our four elements (given a choice of representation of

), and we can minimize this loss function with standard algorithms such as SGD or Adam.

We note that using a compact group like comes in handy for this task since we can run backwards propagation with constant memory, meaning not depending on the sequences’ lengths.

Another potential application of the functions introduced in this piece is predicting tokens in a language model. Continuing our DNA example from above, we can take our loss function to be that of measuring the distance between an embedding of a subsequence of DNA and the embedding of its next nucleobase. Optimizing this loss function might give an interesting “language model” for DNA, though I haven’t done any experiments with this yet.

Conclusion

This piece has introduced a family of algebraic locality-sensitive hashing functions, that as far as the author is aware, is new. These functions can be interesting for a wide variety of contexts, such as hashing strings, images, time series, and general multi-dimensional arrays of fixed or varying dimensions. In contrast to MinHash, the functions are algebraic and differentiable, so optimization can be applied to their choice, and they should be performant on modern hardware such as GPUs.